37th Gawad Alternatibo OMNIBUS REVIEW

37th Gawad Alternatibo OMNIBUS REVIEW

The Gawad CCP Para sa Alternatibong Pelikula at Video, commonly referred to as Gawad Alternatibo, remains a testament to the enduring power of alternative cinema as a space for voices that push, question, and reimagine. Across narrative, experimental, documentary, and animation short films, this year’s lineup brings together works that move away from familiar formulas and instead sit with stories that are often overlooked, uneasy, or hard to pin down. These films are grounded in lived experience, shaped by personal, political, and social realities, and made with an intent to question how stories are usually told. For 37 years, the Gawad Alternatibo continues to champion alternative filmmaking as a form of resistance.

This omnibus review gathers critical reflections on the four categories: Narrative, Experimental, Documentary, and Animation, each offering distinct approaches to understanding social realities while collectively underscoring the role of cinema as both witness and intervention. Taken together, the selections reflect different ways of working within alternative cinema; the narrative shorts focus on character and place, drawing from everyday struggles and intimate moments. Experimental works break from structure and logic, using form itself as a way of thinking through present anxieties. Documentary films turn their attention to communities and issues that remain at the margins, tracing how larger systems affect ordinary lives. Animation opens another space entirely, using imagination and visual play to approach memory, loss, and possibility. Together, these short films remind us that alternative cinema is not a genre but a practice: one that insists on seeing, listening, and imagining the nation in its current crisis. Here are the reviews for the featured finalists on Cinemata on Narrative, Experimental, Documentary, and Animation categories of the 37th Gawad Alternatibo:

Narrative Category

Official Publicity Material of the 37th Gawad Alternatibo Narrative Category Online Streaming on Cinemata | Courtesy of Cinemata

Si Balong at Si Doro

Directed by Jenser Recosana

Eccentric friendships are fascinating but not new. In films, it is one of the most revered genres in the film industry. This is reminiscent of those of Bong Joon Ho’s Okja and Paul King’s Paddington. Jenser Recosana’s Si Balong at Si Doro tells the friendship of a hardworking young boy, Balong, and a carabao named Doro, which he tends to for his work. Balong’s character is kindhearted and of a caring nature. His caring nature shows in the way he takes care of his father, soaks the cloth, and wipes his arms to clean him. Due to his father’s declining health, he has no choice but to give up his companion Doro and sell him to acquire more money dedicated to his father’s illness. He scours from house to house, friend to friend, stranger to stranger in search of a willing patron despite his feelings. When he successfully finds a new owner for Doro, Balong finds himself in despair. The carabao, although unable to talk, shows its sympathy with the man who has taken care of it. In those moments, their friendship was the only thing that mattered.

Film still from Si Balong at si Doro

There is something almost spiritual in having formed a bond with an animal. It is the kind that only speaks within our minds. A kind of attachment wherein no words are allowed to consume. Sometimes the simple act of existing, of being together–a companion–is what makes it more meaningful. This is the kind of attachment that not everyone has to understand; the same goes for Balong and Doro. There is no question as to their friendship.

However, Balong and Doro’s friendship was just the surface of it all. The lack of accessible access to healthcare, which intersects with the long-standing issues of resiliency due to poverty, was amplified in Balong’s father’s situation. Even the rich's impunity cannot be escaped here, as they start taking away more land from the farmers. These problems continue to seep in — piling up and undeniably being ignored — like the story of Balong and Doro. — Yve Ventures

No More Crying

Directed by John Peter Chua

There is no easy way to discard guilt; it feels similar to a leech that latches itself onto you. Sucking and sucking in the blood and life out of you until it is no longer bearable. How do we apologize to someone who is no longer with us? John Peter Chua’s No More Crying tells a story of grief in search of the answers to those exact questions. Refusing to visit his Ahma before her passing, he navigates through his feelings of sorrow and mourning as he goes through a trip down memory lane in search of a photograph he could use days before her funeral. This is a film that is a meditation on grief, loss, and untimely guilt.

Film still from No More Crying

“And now? Would there still be a next time?” Scenes of missed opportunities would constantly replay inside a person’s head like broken melodies. The reality, however, is that there is nothing more we could do. Guilt may just be an uncompromising feeling — but maybe it exists; maybe it breathes through our lives because in our tempestuous desires, we care. Whether there are many shortcomings, guilt exists because we care enough to feel it. Regret is just another feeling we must learn to cope with in this ocean of mourning.

The film shows a part of the roof of their house falling from the heavy rain, the stack of things pillaging through various corners of the house, all these things that are hardly rummaged through, though, unironically, make it feel so homey. But this space exists, this quiet thin fold of sadness in the atmosphere is belching — it is hard not to notice. — Yve Ventures

ang pagbukod ni melmel

Directed by Nathaniel Amor Turingan

Until when is sacrilege tolerable when it now becomes an outward extension of abuse? Until when is the preservation of culture revered when it has meekly turned to outwardly perpetuating harmful and debilitating repercussions? In a tribe somewhere in the southern part of Palawan, female children are contracted to become brides. Drafted into this karmic fate that they must face all for the sake of tradition, Nathaniel Amor Turingan’s ang pagbukod ni melmel takes a glimpse of what it is like for a little girl to navigate through life along these unwanted consequences.

The film follows the life of the protagonist, Melmel, who is in her teenage years. She is seen frequently at the ocean, gazing at the horizon, and wondering what’s beyond there. Melmel loves to dance on that very shoreline as well. Just like any other being, she has a dream of her own, has a partner she wishes to be with, and has a life she hopes to attain, but just like any other woman in her tribe in her early years, she is also one of the hundreds of women who is bound by the same fate — to be married to an older man.

Film still from ang pagbukod ni melmel

Most traditions are patriarchal in nature. For decades, it has always been women who have had to be forced to change out of their dreams, to sacrifice, and to carry their young. This film sheds light on a tradition that must be reexamined in today’s ethical gnosis. Until when will we allow for such things to happen? In Melmel’s perspective, the only way she believes she could break free from everything and provide herself with her own agency is to escape this very place. And she did. Melmel chooses to leave this life behind for good.

Nathaniel Amor Turingan’s ang pagbukod ni melmel tells a powerful story about having authority over oneself in a place where you’re not allowed to. It teaches us to make a choice even in cases where we don’t have one — just like Melmel, who chases another life, and runs away from the clutches of her family traditions, because she wants to dance, because she will, and because she wants to. — Yve Ventures

Angela and Her Dying Lola

Directed by Mark Terence Molave

When we look back on the initial moments of our lives, when we find pieces of our youth or when we look for the first affectionate palm that’s ever held our body, where does our mind initially go to? Who do we look for? Mark Terence Molave’s Angela and Her Dying Lola tells the story of a young girl named Angela, or more commonly known as Gel, who is forced to leave her childhood behind and find ways to take care of her ill grandmother and keep both of them alive. With such a heavy responsibility instilled in her at such a young age — the events in Angela’s daily life — aside from taking care of her grandmother, have escalated to rationing their food for the month, looking after the house, and finding other ways to put food on the table.

Film still from Angela and Her Dying Lola

One tradition the Filipinos are very keen on is putting family at the very core of life. We are taught to love them the most, to take care of them wholeheartedly, and to be with them when things are difficult. However, for Angela, familial relationships require a complexity she has yet to understand. Having no one else to rely on, Angela is forced to grow up. She endures her uncle's offensive and below-the-belt remarks so they could have money to eat by the end of the day. Other than the dysfunctionality of their family, another truth sheds light on Angela’s lost youth, and that is surviving amidst poverty. It steals lives, it takes away opportunities, it tramples and tramples on people until there is nothing left of them to hold on to.

The love between Angela and her Lola, her dying Lola, is nowhere within reach of superficiality — it is, however, safe, sacred, and final. There is comfort, but also unyielding sorrow. There are small acts of happiness, but also fleeting ones. Nothing is left but the cycle of life and death, one must become accustomed to. Towards the end, Angela is shown eating her meal — a full meal. She no longer has to ration her food or scour for medicine. She now sits at the edge of the brown wooden floorboard — with her mouth full, and a space noticeably bigger and colder than it was yesterday. — Yve Ventures

Hoy! Pradah Ko 'yan!

Directed by Myka Jeanell Arabit

The Pradah — a symbol of fashion, taste, and wealth. This is what Khay Eva’s character, Phearl, believes in. Strutting the streets with her carefully picked formal attire and her red-clad 6-inch high stilettos, Phearl believes she can achieve anything with these heels — even getting herself out of her current unemployment status. But what will happen to Phearl when, right before an important interview, she loses this very pair of shoes? Myka Jeanell Arabit’s Hoy! Pradah Ko ‘yan takes its own spin around the adamant need for people to pressurize themselves and succumb to a society wherein self-presentation matters, and looking good is a landmark for labeling people into increased social statuses.

Film still from Hoy! Pradah Ko 'yan!

Packed with modern-day comedic references, the film utilizes such lines to entertain the audience. The visuals are ornamented in bright colored hues, from the clothing to the house’s interior; every single frame is made for the audience to resist forming into their candy-eyed expressions. This film is staged to have a fun and lighthearted undertone to it, all while still being able to successfully convey a message. Khay Eva’s performance as Phearl Calios is humorous and remarkable.

It is a known fact that the realities of having to put yourself out there in a dog-eat-dog world are not easy. Phearl ties her success directly to a pair of red shoes, as she believes they are her only source of hope for a better future. Something out of the ordinary, something she wouldn’t usually have, something the rich could easily acquire hundreds or even thousands of. When Phearl loses this, she desperately tries to find it. It is not that the red shoes will make her pass an interview, but because it is the red shoes that will give her that confidence, that skin-numbing decision that could either make or break her future. It is her final ounce of belief in the shoes that lets her see that single glint of light in her life called hope.

Arabit’s satirical take on this film is one that does not arise without having borne the effects of late-stage capitalism. This is merely a manifestation of the bearings of a capitalist-induced and functioning society. — Yve Ventures

Laglag

Directed by Gian Carlo Ducusin

Anti-abortion became a popular topic for this year’s lineup, and also this short film. Though not directly about abortion, its visual depictions of an unborn child suffering add to that debate. But the film focuses on the complexities of a woman’s decision to have an abortion. Gian Carlo Ducusin’s Laglag depicts this complexity through vivid imagery of an unborn child and imagined conversations between the unborn child and his mother.

Film still from Laglag

Maria had already set from the start that she wanted to get an abortion, but while waiting for the day to come, she had imagined conversations with her unborn child. These conversations depict Maria’s potential to become a mother as she shows signs of care. But when Maria tells a bedtime story to her unborn child, her filtering and refusal to explain some parts of the story already show how cruel the world would be if her unborn child were to be born. Maria was already aware of this, but she kept doubting herself about the potential future and life with her unborn child. Abortion is illegal, and practices from faith healers are not safe, which adds to the fear for her life.

It was revealed that in the end, Maria was still very young, but she made a decision that would be best for her and her unborn child. Maria had doubts, but she’s not to blame for how she was brought up, and the fact of how illegal abortion is causes her to also doubt the process. But in the end, these emotional experiences and living in uncertainty, where there is no moral and legal process it add to the complexity before Maria could finally decide. Ducusin’s Laglag humanizes these experiences of doubt that women faced in times of uncertainty. — Christ Dustly Go Tan

Maria

Directed by Chris Jan Vergara

Young women are always faced with the heavy burdens that they themselves have no control over or did not even want in the first place, but societal values and culture can make them think otherwise, that those incidents that occurred to them can be reconsidered as something good or added to their identity and value as a woman. Chris Jan Vergara’s Maria sheds light on these factors that still keep young women from considering abortion, hindering them from considering it.

Film still from Maria

The short film is set in a remote village on the island of Negros, which already sets the impression of provincial innocence, where access to sex education or even modern ideas is limited. But despite this remoteness, religious influence is still dominant as throughout the short film, she was contended with religious guilt for trying to abort. Conversations of death, murder, and hell are a recurring topic throughout the short film, as it was an effort by the ghost child to instill guilt in Maria, the main character, for trying to get an abortion. It’s also interesting that it was only the faith healer, whom the ghost child called a demon and who gave Maria an abortion medication, was the only one who recognized the grave responsibility of carrying a child and how Maria is still not ready for it. The only one who could have helped Maria was vilified.

When the spirits of children started to tell their aspirations in life, it always ended with the fact that it was their mother who killed them. It is important to consider that at the end of the short film, it is an injustice that it is always women to blame for abortions and not their rapists. Another worthy detail is how the short film ended with a note of illegal abortions, which already adds fear and doubt towards the practice of abortion, as it is illegal, as they rely on faith healers for these. The uncertainty of these practices also becomes the catalyst for these kinds of narratives. Vergara’s Maria is more than its anti-abortion depictions, but it explores why anti-abortion became a dominant narrative. — Christ Dustly Go Tan

Metapora

Directed by Renil Frankie Badango

Following one’s passion in life becomes a hidden personal paradise that anyone can retreat to. This offers a peace of mind that everything will be fine as they have already done the things that they wanted to do in life, the things they loved. However, society today has evolved to the point where these passions in life are now turned into demanding labor, a means of income. This deprives the idea of a refuge of peace as the one thing that they’re passionate about became the very thing that causes them anxiety and to struggle to meet their client’s standards and expectations, causing them to feel burned out from their passion. Renil Frankie Bandango’s Metapora explores this phenomenon of burnout culture and its manifestations towards personal and physical degradation.

Film still from Metapora

Burnout is a draining process, and it’s chronically felt throughout. It gives thoughts of worthlessness and a dreaded obligation just to comply with one’s expectations. Nico used to be passionate about writing, which made him pursue this passion, but demands and expectations are usually rooted in satisfying a capitalistic market, which changes his perspective on his passion with cynicism. Nico used to have a paradise refuge in his mind, which he usually retreats to when writing, but that idea of paradise is now destroyed. Because of the demands, Nico struggled with health, sacrificing eating and sleep, and often has nosebleeds, which causes his sister to worry for him. Nico’s succumbing to madness is a manifestation of burnout taken too far, as things he used to love doing now feel like an obligation, and everything that just nags him is just a nuisance to it, dismissing their intent of care toward him.

To be content with burnout also means killing your passion, now deprived of life, and now just a product of capitalistic demand. Nico is never satisfied with his work, and the only one who is satisfied is his client. Nico’s burnout turns his passion into an exhausting experience just to meet demands. Badango’s Metapora makes one feel resentment and unable to cope with this redirection of perspective in their life. — Christ Dustly Go Tan

Pietà

Directed by Dylan Margarette Cerio & Johnfil Crisjim Nunez

Mama Mary became the ideal role model for mothers, giving a picture of what motherhood should look like. She embodied grace and compassion and even raised Jesus, to whom he is popularly known, and this is attributed to Mary’s effort as a mother. But what happened to Mary was not what every mother wanted to be like; she lost her son. Dylan Margarette Cerio’s and Johnfil Crisjim Nunez’s Pietà recontextualizes these ideas of motherhood of Mary into the mothers of victims during the drug war.

Film still from Pietà

Losing a child is a mother’s worst nightmare, a trauma that lasts for a lifetime, a long time. In the time of Duterte’s drug war, this was the time of everyday killings of innocent victims, and it created a culture of impunity, and this violence is now normalized. In effect, families would have to worry every night if something happens to their loved ones, as the drug war doesn’t choose its victims for its quota system. Even after the drug war, families haven’t received the justice they deserved for their slain loved ones, as the ones responsible for the killings have not yet been held accountable and are still being delayed, causing the families to struggle to grieve and fight for justice.

Mary may not worry too much for her child as Jesus is protected by God, but this doesn’t go the same for every mother who has always lived in constant fear, worrying if their children can still go home safe during those times. The thought of God protecting them became a false hope, as man is now capable of taking away life, and if the perpetrators can get away with it, then what’s the point of clinging to hope? Cerio and Nunez’s Pietà argues that Mary may be the ideal mother, but no mother wants to be like Mary, to lose a child. — Christ Dustly Go Tan

Watch the 37th Gawad Alternatibo Narrative Category at Cinemata now!

Experimental Category

Official Publicity Material of the 37th Gawad Alternatibo Experimental Category Online Streaming on Cinemata | Courtesy of Cinemata

Nakakapagpabagabag Kapag Kinakabag Ka

Directed by Earl Justin Cruz

This is a visually minimalist film that focuses on a resting ‘nuno sa punso,’ or an old dwarf-like nature spirit in Filipino mythology. For the whole short film, we only see its head (Kyle Lazaro) as it reacts to the situations around it. Most of the direct storytelling of the film is in the conversations we hear or read about in the subtitles. It’s split into three parts, with the first two detailing the experiences of locals peeing on the nuno and getting into problems because of it. The third shows the nuno erupting into anger at what the film is perhaps alluding to as the worst form of disrespect towards it, the encroachment of the Chinese on Filipino soil, as represented by the controversies around Alice Guo.

Film still from Nakakapagpabagabag Kapag Kinakabag Ka

It’s a playfully-told short that exemplifies the notion that one doesn’t need a large budget to be able to express oneself creatively — and with cultural, mythological, and political themes to boot. This film does all of that and with a good sense of humor as well.

This is likely not very important, but the Chinese characters at the end should have probably been in simplified form if they were meant to allude to China, as the traditional form featured in the film is only being officially used today in Taiwan.

Ang Saad Nga Bugas

Directed by Mikone Joshua Calungsod

Ang Saad Nga Bugas is a film that protests against the administration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. for its failure to lower the cost of rice as was promised. The short opens with an audio excerpt of one of Marcos’ speeches, claiming that he dreams that the price of rice could be dropped to 20 pesos. It’s juxtaposed first over rustling fields, then over an array of rice bags whose price tags are ever-rising. It immediately sets up its themes within the first minute. And the rest of the short functions more as a meditation on them. We see the life cycle of rice play out in short bursts, with sound design carefully syncopated to produce a growing, eerie anxiety— thumps, shuffling, garbled voices, and wails. Then a flurry of images that end with the burning effigy of a farmer. Across the field behind them looms a large construction site. Perhaps the film suggests that it is the farmer who suffers most by the failures of this regime, that it is the farmer class as a whole that is being killed off by it. In the background, we hear a second speech decrying the president, that he was “lying through his teeth to get the votes of people.” Oddly, it’s the voice of Vice President Sara Duterte, clipped from her viral live-streamed press conference, where she claimed to already have orders set up to kill Marcos if she’s assassinated first. The short ends with the Bagong Lipunan theme song playing over clips of burning rice.

Film still from Ang Saad Nga Bugas

Interestingly, the film pits Marcos and Duterte on opposing ends, while siding with the message of the latter. This is notable because the more common media interpretation of that press conference characterized Duterte as unhinged, while this short seems to imply that she actually had some important points of criticism against Marcos. I also find it interesting that the film focuses on the rise in prices of rice as it connects to the lives of farmers, as, from afar, it would seem like lowering the price of rice would actually lower the profits of farmers. Or perhaps having lower prices of rice may signal that farmers are being forced to undercut themselves due to more competition with rice imports. Ideally, the government would provide more support through subsidies for local rice producers, but all of this, of course, is beyond the scope of this review and more complicated than can be simplified in any short. Perhaps the film is trying to show that, amidst all of this elite-infighting, the farmers suffer either way. They are never legitimately on the minds of those who want to rule. It’s all rhetoric for votes.

Hinimo Ka Gikan Sa Yuta, Ug Sa Yuta Ka Pauli

Directed by Gab Rosique

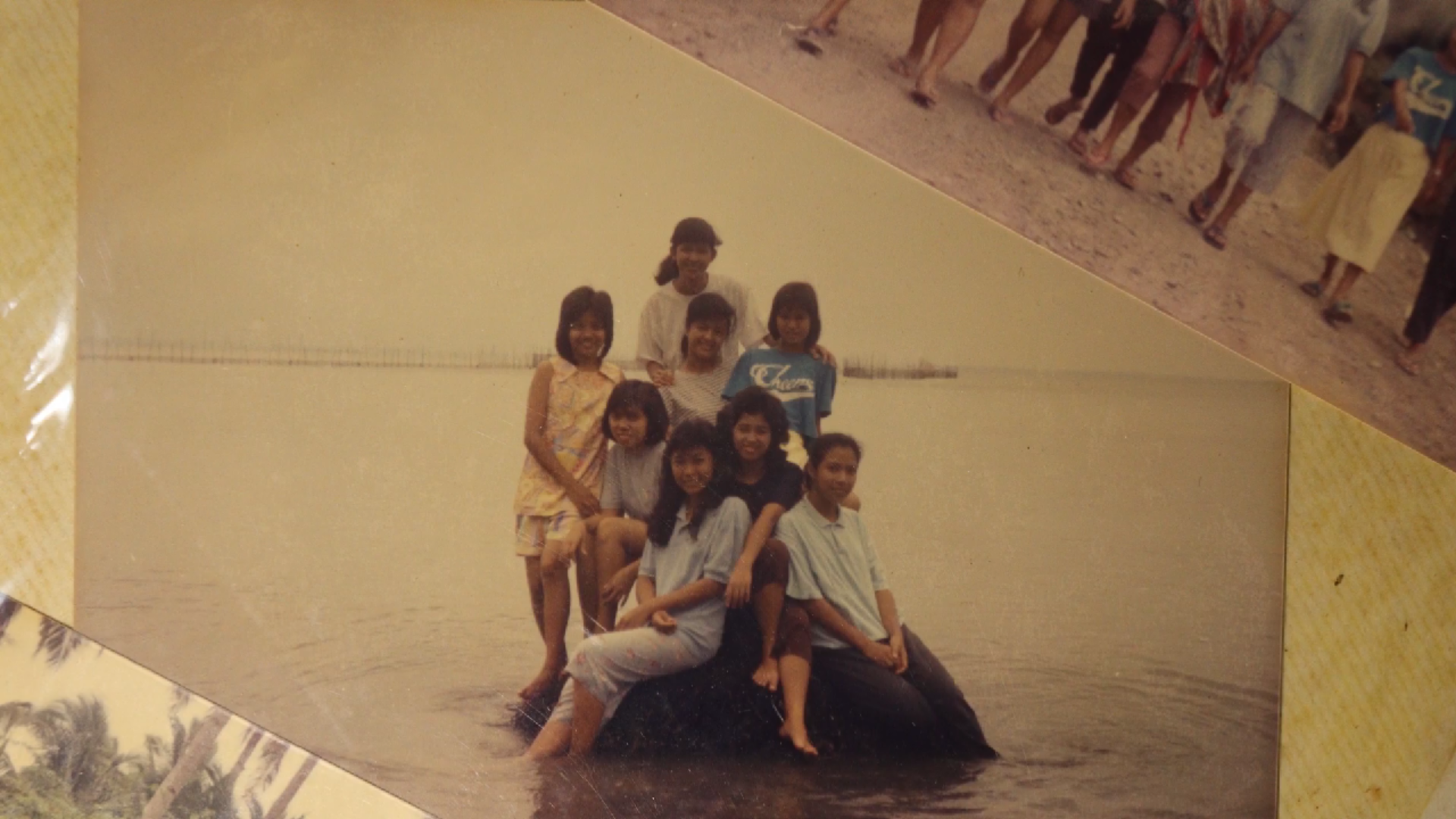

This film is an ode to director Gab Rosique’s mother. It functions both as an exploration into her life and as a reflection on how it reflects on his. Most of the film consists of photographs of different stages in the director’s life, from his early years to his current state today, paralleled with that of his mother’s. Throughout, we see decades-old portraits and documents and childhood essays, all edited together at a frenetic pace. Various videos are projected onto the director’s bare body; shots close in on his eyes, neck, and back, as shuttering neon-lit landscapes flash over them. Perhaps they’re memories externalized on his skin. There’s a lot more going on here. It’s all very personal and expressionistic. Rosique clearly has boatloads of creativity trying to burst out of him. Leon Pavia’s gently propulsive ambient score also lends itself well to the introspective mood of the whole film. It’s all done quite well.

Film still from Hinimo Ka Gikan Sa Yuta, Ug Sa Yuta Ka Pauli

I will say, however, that films as personal as this can sometimes run the risk of losing their audience when they’re presented without a clear hook. Perhaps as someone who makes a film about their mother, it doesn’t make sense to think about it through this lens. I don’t really think it’s necessary. But from an outsider’s point of view, it is possible to see a film like this and wonder why one should care in the first place. Watching the film, one pieces together that it’s about the protagonist’s relationship to himself and to his mom, but that isn’t intrinsically interesting for a stranger. It can sometimes feel like flipping through a photo book without any context. Compared to other films with similar conceits, like Sophy Romvari’s Still Processing (2020) or Zhang Mengqi’s Self-Portrait with Three Women (2010) (which also includes extended scenes of videos flashing over the director’s naked body), we don’t learn much about the images and videos here. Even a little bit could have gone a long way to extending its reach beyond the self. But of course, none of this really matters. I watched it and was moved, and it reminded me of my relationship with my own mom, as I’m sure it has for the many others who’ve seen it. And perhaps that’s powerful enough.

Tirik

Directed by Wika Nadera

Tirik is the thesis film of artist Wika Nadera, and it stars his Palanca-award-winning father Vim Nadera, who is also credited as the short’s writer. It follows a melancholic old man visiting a rundown cemetery in Tayabas, Quezon. While we see him walking around the area, we hear him in voice-over passionately reciting a poem as if in a spoken word performance. It appears to be autobiographical, dedicated to his son Awit, who died of pneumonia at only four years old.

Film still from Tirik

The poem is the main throughline that holds the film together. It’s very literary and full of striking imagery and symbolism. It almost overpowers the rest of the elements of the film, as they struggle to always match the poem’s intensity. This is not to say that the film is particularly lacking visually — it’s actually filled with astonishing shots — it’s just that there seems to be a lack of balance with its elements. The poem is so emotionally charged and lyrically dense that listening to it draws all your attention to your sense of hearing, with your eyes perhaps peering mostly down to the subtitles to catch all of its meaning. It doesn’t feel possible to appreciate them at the same time. The visual elements feel more like an accompaniment to the storytelling of the words rather than a central element you need to pay attention to. Maybe that’s alright. But could it have used more moments of silence to allow its images to speak for themselves? To allow the audience to better process the power of its poetry? To give us a chance to take everything in?

As it is, it’s still a moving short film anchored by a vivid, heartwrenching poem — a worthy memorial to a lost sibling and son, and the cemetery that housed him.

Genesis

Directed by Jay Borilla

This film is an abrasive and ambitious short that defies direct description. It’s said to be about the “seven phases of existence,” presumably of a disillusioned Filipino youth overwhelmed by the absolute mess of our political system. It starts with words from the book of Genesis — “let there be light,” then we see a pixelated human figure walking through a field of digital distortion. Next, a student, perhaps the same person, now walking across an actual field, while drawings of politicians in the style of editorial cartoons flash across the screen: Bongbong and Imelda Marcos, Sara and Rodrigo Duterte, and more. They’re having an orgy. Later on, in perhaps the short’s most grotesque scene, bloody ejaculate is expelled onto printed photographs of President Marcos and Iglesia ni Cristo Executive Minister Eduardo Manalo. Then we see webcam footage of the director wiping something on his face as he drowns in memes. It ends with a video clip of perhaps the director as a child, celebrating the upcoming new year, closing the short with fireworks, a call back to the opening lines of light.

Film still from Genesis

There are a lot of vivid ideas packed into this short’s five minutes to relay the feelings of frustration with Philippine society that I’m sure most young people feel today. A lot of its energy comes from its violent editing and unique sound design. It sometimes even feels like a music video for the intricate soundtrack itself, which incorporates tracks from Yeule, Brockhampton, Black Dresses, and Kanye West, among others, to tell its sonic story. It all works together to relay the helplessness many of us feel amidst the absurdity of living in a country whose politics is directed by what many believe is a cult. It was so intense it made me physically cringe in my seat, which is more than appropriate for all that’s been going on as of late.

Parapo

Directed by Jhonny Bobier

This is a dark and nihilistic depiction of the horrors of Philippine society condensed into a mysterious jeepney ride through the wilderness. It’s sort of like the latter half of Darren Aronofsky’s mother! (2017), where everything spirals into a mythical hellscape, except without any of the buildup towards it. And so what you’re left with is a series of graphic and disgusting scenes of depravity, a lot of which borders on sacrilegious. It opens up with a jeepney driver wearing a barong tagalog and a pin of the Philippine flag violently humping the ground. And that’s just the start of it. Among the passengers in the ride is a man masturbating behind a Bible and a woman who lustily licks a statue of the Virgin Mary. At some point, the driver leaves the vehicle and eats a heart while blindfolded. He returns to the jeep and continues to drive on, blind, until the only innocent passenger, a young boy, finally leaps out and escapes, crying out to the skies.

Film still from Parapo

This is a disturbing film that successfully uses the elements of cinema to trigger some strong negative feelings. Its claustrophobic setting is mirrored in its chaotically dense sound design. The constant wailing from the jeep’s passengers is nauseating. And by the time the film ends and the child runs off, I wanted to as well. And so I think the film does what it’s trying to do quite well. But does it give me a new perspective on the country? Has it made me reflect on our issues and how to solve them? Has it inspired me with hope or ideas for how to get out of our situation? Does the film make sense on its own without any outside knowledge? Did I find all of its allegories meaningful? Did I even enjoy watching the film? To all of those, no. But I still think it’s a well-made provocation to feel more intensely what many of us have perhaps suppressed, living in this country. And so for that, I think it’s worth watching.

Wanted to Say but You Typed It Nalang Sa Socmed

Directed by Ja Turla

This film juxtaposes Filipino comments on a livestream of the 2025 papal conclave with an assorted collection of humorous clips, among which is a three-minute recording of someone playing Subway Surfers. Each of the comments is shown in what looks like chronological order and is read aloud by an automated CapCut voice.

Film still from Things You Wanted to Say but You Typed It Nalang Sa Socmed

I appreciate the idea of wanting to capture a snapshot of Filipino online comment culture, as it can say a lot about how many people here process the world, but I found it a little too chaotic to follow. My interpretation is that the film is meant to make us feel as if we were reading the comments ourselves in real time, up to the act of playing games out of boredom while waiting for the results to come in. However, I found the audiovisual experience of it to be too distracting to be able to make sense of what was going on. I had to watch the film again with the sound off to be able to better appreciate the relationship between its words and images. Overall, it’s still a memorable effort at trying something different. And I think that it was at least successful at capturing and bringing to life this very specific moment in time.

We Were Here, Where We Wear

Directed by Edsel P. Gasmen

This is a film about the toll of the fast fashion industry on the environment. It’s straightforward, starting off and ending with texts describing the whole message of the film. It features a woman taking selfies of her outfits juxtaposed with images of African landfills filled with clothes thrown away. We are also shown mirrored shots of her own clothes piled up in a field or thrown into rivers. Some scenes also depict her literally choking on the clothes, perhaps to represent how it’s destroying all of us as well.

Film still from We Were Here, Where We Wear

It’s definitely important to be reminded of the harms of fast fashion, and it’s good that young filmmakers today think it’s vital enough to make films about it, but I think this short could have explored this topic more deeply. Its critique of social media outfit-of-the-day culture is relevant and timely, but it’s necessary to consider the underlying roots of the popularity of fast fashion, especially in the Philippines: it’s cheap. The reason why many buy sweatshop-made clothes is that their economic situations do not allow them to be more ethical in their purchases. Yes, the promotion of consumerism in social media trends is a part of the problem. But if one wants to face this issue head-on, one cannot forget the role of economic inequality. Or perhaps if one wants to focus specifically on fast fashion, it could be useful to help us understand what exactly defines fast fashion and which specific companies we should avoid. Or perhaps it could have been useful to be more specific about how this relates to the Philippine experience. Perhaps more statistics on our production and consumption of fast fashion, how our lands and oceans are also used as trashfills by other nations around the world, instead of just general statistics about the global fashion industry. Why did this film have to be made by a Filipino? Or by this specific filmmaker? What does this add to the conversation?

These are all probably way too much to expect from a short film, but I think it’s good to at least think about these issues more deeply if one wants to make political art about them. But remember that it’s already a great first step to even care about this, so the work one continues to make about it can only get better from this point on.

Watch the 37th Gawad Alternatibo Experimental Category at Cinemata now!

Documentary Category

Official Publicity Material of the 37th Gawad Alternatibo Documentary Category Online Streaming on Cinemata | Courtesy of Cinemata

Romeo and Julie

Directed by Ysamae Yrrah Carelo & Edward John Louis Factes

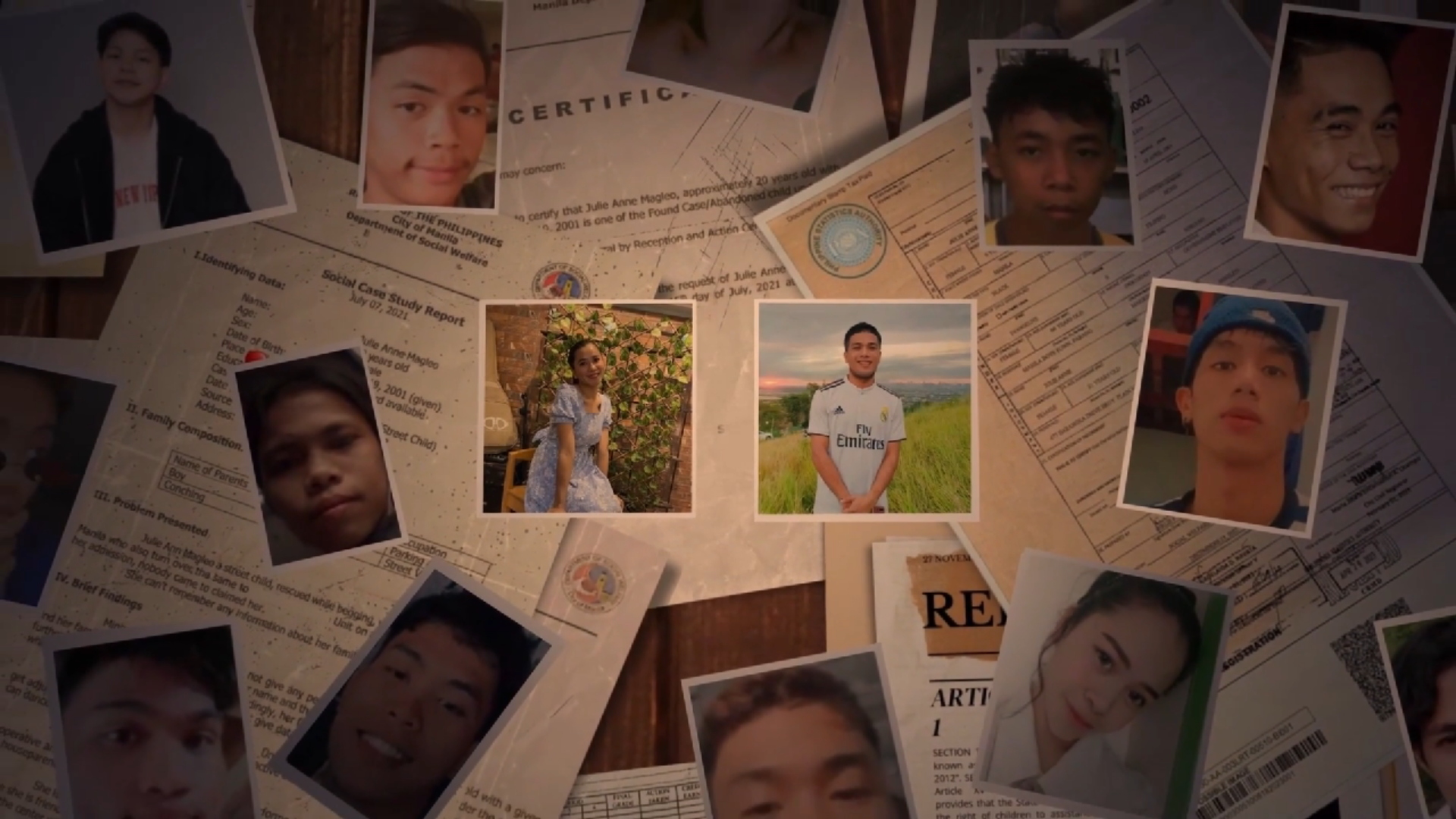

The world nowadays works around legal recognition, meaning everything has to be formally recognized under the government’s bureaucratic process, and if some people cannot comply with these processes, they won’t be granted any government services. A birth certificate is more than just a piece of paper, but it serves as proof of someone’s nationality, existence, and identity. A birth certificate is already detrimental to accessing those services from school and even employment, but how does one grapple with life if they don’t have a birth certificate? Or even worse, they don’t know who their parents are. Ysamae Yrrah Carelo & Edward John Louis Factes’ Romeo and Julie gives light to one of society’s overlooked problems, the case of foundlings and their struggle for identity and legal recognition.

Film still from Romeo and Julie

The short documentary navigates Romeo and Julie experiences as foundlings and their struggle for identity. It was already straightforward that the consequences they were about to face for having no birth certificate were that they would be denied access to government services and enjoy life that requires legal matters. It was already traumatizing for them to be abandoned when they were still children, and they are now recognized as floating people who have no legal identity. It’s a difficult watch to see how opportunities came flying to them, but they can’t accept or process it due to the lack of a legal identity, depriving them of a life they could have had.

Knowing these experiences, being granted a birth certificate means they were granted a national identity and that they are legally recognized as a person now. They can finally enjoy the things that every person can. The short documentary brings that weight of finally being recognized after years of struggling with these experiences. Carelo and Factes’ Romeo and Julie not only unearths these experiences of foundlings but also exposes the bureaucratic process that continues to delay and deny people the legal recognition of being a person.

Daungan Ng Mga Naghihintay

Directed by Kaila Arvi B. Ariston

The short documentary fixes its gaze on the West Philippine Sea with a clarity that feels steady but not cold. It treats the sea as more than a backdrop. It stands as a field shaped by patrol boats, stalled talks, and lines drawn far from the people who depend on it. The film stays quiet about politics, yet it shows how each move in the dispute pushes into daily life. You sense how every shift in the tide of claims presses against the families who fish these waters. In that view, the sea stops being an abstract point in long debates and turns into the thin space where hope meets danger.

Film still from Daungan Ng Mga Naghihintay

The interviews carry this truth in plain sight. The director stays close enough for you to feel how each mother holds her worry while the country argues over rights and borders. Their voices bear the weight of a conflict they never chose but must live with. The film shows what headlines miss: that the West Philippine Sea dispute slips into kitchens, prayer rooms, and the empty chairs left after every lost trip. It shows that each patrol and policy lands on a family waiting for someone who might not come back. The devastation sits in that wait and stays with you even after the film is over. — Jessica Maureen Gaurano

Eyen Kami Deyuhan

Directed by Regine Mae I. Manuel & Charles Dewey Vitto

Eyen Kami Deyuhan follows the Dumagat people at a time when their land is under steady pressure from soldiers and newcomers. The film stays close to Kuya Rolly and his family. It shows how their work, worries, and choices sit inside the long fight to guard what they still hold. It does not turn their struggle into a spectacle. It stays with them and lets their own rhythm lead the scenes.

Film still from Eyen Kami Deyuhan

For the Dumagat, the land is more than soil. It keeps their past, their bonds, and the way they see themselves. The camera moves with them through homes, forests, and fields. You feel the weight each time a patrol passes or a notice of removal lands in their path. Quiet talks, small tasks, shared meals, and the way they guide their children all hold their story. These moments show how people keep their ground even as the world around them shifts. What stays with you is the truth that the Dumagat face each day with risk close by and resolve just as near. Their fight does not stop, and neither does their will to stay on the land that shapes their life. — Jessica Maureen Gaurano

Dagiti Nalaga Nga Istoria

Directed by Melver Ritz L. Gomez

The film follows the lived stories of the Tingguian basket weavers of Uguis, Nueva Era, Ilocos Norte, Indigenous women whose steady hands shape baskets that hold the rhythm of their community’s craft. They work with scarce materials and the weight that sits on their shoulders, yet they keep a practice that calls for patience and strength.

Film still from Dagiti Nalaga Nga Istoria

In the documentary, the baskets rise beyond their use. Their forms and fibers, along with the choices set into each pattern, show what the weavers seldom say aloud: memory, labor, and the quiet push to keep a tradition alive. As the film stays close to the women, through their routines and through the slow steps of weaving, it shows how each basket carries a part of Tingguian identity, passed down, reshaped, and held toward the future. The short documentary refuses the pull of nostalgia and treats the craft as a living practice that feeds both culture and community. It stands as a tribute to the weavers, whose work keeps Tingguian heritage rooted in a landscape that shifts around them. — Jessica Maureen Gaurano

Agawan Sa Pamana

Directed by Quert Magtibay

Lack of spaces has always been an issue when development nowadays focuses too much on building too much to the point that there are still a lot of marginalized sectors that are least prioritized, and no spaces are left for them, as everything is geared towards business and profit. Even if there were still spaces, there are only a few allotted for recreational activities, many people would have to fight for them in using it, from dance rehearsals, zumba sessions, or even the country’s favorite sport, basketball, but there are some sectors that are negatively viewed by society, which discourage or even ban them from using it. Quert Magtibay’s Agawan Sa Pamana shows this struggle for spaces from the perspective of society’s vilified sport, skateboarding.

Film still from Agawan Sa Pamana

The short documentary was able to show both sides of the coin, where one would see the culture of skateboarding flourish, and at the same time, the bureaucratic process for this to be implemented. The problem is multidimensional; one would only wish skateboarding to remain in its practice, while the other wants to formalize it as a sport. There were stereotypes projecting towards skateboarding, as the LGU would rather focus on developing areas for basketball, no questions asked. The Lambanog Skate Crew doesn’t wish it to be formalized because it makes skateboarding more restrictive, deprived of its usual aesthetics of street culture. Despite the many hindrances, they remain resilient and still try to comply with the bureaucracy of the LGU, but in the end, they are still denied.

Their wish was simple, and it was to give them space to play. They were left with no choice but to create a space for their own, no matter how little it is, but still theirs. They can no longer wait for the LGU to bring it to them, as they don’t consider this a priority. The short documentary emphasizes how important this culture is to them and how this culture builds communities that they can call home. Magtibay’s Agawan Sa Pamana highlights that the perseverance and love of the Lambanog Skate Crew for skateboarding is also a fight for their identity and culture, and they’re doing everything in their capacity to still mark a space for it, no matter how small that space is. — Christ Dustly Go Tan

NOMO KWEEN: The Last Woman Standing

Directed by LA Oraza

The short documentary takes a fresh look at the life of an influencer. It’s funny in a way that catches you off guard, since the format often leans toward heavier stories. Here, the film holds a loose and odd rhythm that fits Stella Salle because she is loose and odd in a way that feels warm. The piece doesn’t try to sound deep, yet under the humor and the rough edges, it shows why people connect with her. Her queer humor stays simple and sharp, and younger viewers see bits of themselves in her tone. The film doesn’t turn her into a symbol; it just stays close to her, and that closeness makes her feel familiar and steady in a quiet way.

Film still from NOMO KWEEN: The Last Woman Standing

The skits and jokes work, but the film also lets her slip into small, honest moments; her quirks, her pauses, the way her thoughts jump. Those moments help explain why she’s become a steady presence in her community. She isn’t perfect, and the film doesn’t try to fix her shape or place her on a pedestal. Instead, it leans toward something more real: that there’s value in a person who doesn’t hide the mess. Her flaws don’t weaken her influence; they make her easier to trust. By the end, the documentary turns into a small reminder that humor and honesty can sit side by side without pushing for a loud point. Depth shows up on its own in the spaces where she stops performing and simply stays as herself. — Jessica Maureen Gaurano

Oda Kay Papa

Directed by Johnsep Mari Abode

It’s very difficult to see someone you used to look up to as someone energetic and fun, and suddenly, because of the disease, they have changed, and it made him weaker than he used to be. The thing with Parkinson’s Disease is that it is physically and emotionally exhausting as it involves caring for someone who has difficulty with motor movement and cognitive issues, and it will become worse over time. Johnsep Mari Abode’s Oda Kay Papa navigates this struggle of care and now turns it into a devotion of love.

Film still from Oda Kay Papa

The short documentary navigates the family members caring for Jhun Abode, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. There were a lot of hardships shown when caring for Jhun, and these experiences are emotionally exhausting to the point that sometimes, one would wish that they were dead because who would take care of him if they were gone first, just like how Marites Abodes wishes Jhun to be gone before her. Sometimes it is difficult to be angry with them in their current state of being; sometimes one would get mad at Jhun, but one would feel guilty afterwards because they understand that it is difficult to wish for them to do things normally, but they just can’t, and things can go back to the way it was especially with people with Parkinson’s Disease.

It’s unpredictable, and the emotional toll it brings to see a loved one gradually decline as the disease develops, making this an act of struggle throughout. The short documentary gives weight to this act of devotion through time as equal to the family’s unconditional love for Jhun, no matter what stage they are now. Abode’s Oda Kay Papa turns the struggle of caring with someone with Parkinson’s Disease into an act of devotion and love, a way to get back for everything he has done, and it’s now their turn to return that love to him. — Christ Dustly Go Tan

Padaluyin

Directed by Jhezarie Santiago

Livelihood development programs were made to develop the lives of people, but there are instances where what they imposed as development is not development for the receiving party. There is a mismatch in identifying the needs of the people, especially those from the margins, whose culture is different from those in the urban and rural communities, specifically Indigenous Peoples groups whose lifestyle revolves around the land they live on. Jhezarie Santiago’s Padaluyin questions what constitutes development for the Dumagat tribe from the development imposed by the government.

Film still from Padaluyin

The short documentary tells the struggles of the Dumagat tribe through Joel, a young Dumagat, and his community members, and how they wanted to change things for the betterment of their community. IP groups like the Dumagat tribe are marginalized as well as exploited. Due to the lack of education, they were continuously taken advantage of and deceived, giving them false hopes. Compensation for development aggression from their ancestral lands was only met with development in their definition, such as infrastructures, and providing monetary compensation, or even technical assistance to improve their current livelihood ways, was not even provided, as they think too low of them to handle such responsibilities and technology. The government sees the IP groups as unintelligent and incapable to learn, and they would rather keep it that way so that development aggression programs can continue. The problem is systemic, and its attitudes towards IP groups should change to learning more about their experiences in order to really identify what they really need and what constitutes their development.

For the Dumagat tribe, it was always a communal experience where every action and decision made was for the benefit of the whole community. A lot of wasted potential was shown, such as when Joel mentioned that they wanted to learn how to make their own products and also learn how to transact better, showing their willingness and intent to learn more for their community, but no one is there to provide those services. This attitude is what is absent in most people in urban communities, where they tend to be individualistic, and the short documentary captures the spirit that every member cares for their community and their ancestral domain. Santiago’s Padaluyin makes it clear that these injustices are rooted in their lack of understanding of IP groups, and to end this can start by looking at things from their perspective. — Christ Dustly Go Tan

Si Tes at Si Anggo

Directed by Angelo A. Martinez

When a family member has a chronic disease that needs extensive care, there will be a lot of lifestyle changes and many sacrifices that need to be made to care for that family member. Battling breast cancer cannot be solved overnight, and it’s a decades-long commitment towards making sure that family members can still be comfortable in the current situation they are in. Considering how much time has passed, many things will change, and this includes relationships and family dynamics. Angelo Martinez’s Si Tes at Si Anggo navigates the many sacrifices and hardships they made in taking care of their mother, Tes.

Film still from Si Tes at Si Anggo

The short documentary navigates the relationship between Tess, who has breast cancer, and her son Anggo, who primarily serves as the caregiver for Tess. It’s a lamenting portrait of a family that has sacrificed so much and, at the same time, endured a lot of hardships. Sacrificing their provincial home just to live in the city to continue treatment, and sacrificing more time for caring for Tess, as there is a probable return of cancer. It’s been a decade-long treatment, and things have changed in how they look at their relationship. They’ve gotten closer and would not like to see all their efforts go to waste. It’s no longer easy to let go when someone wants to let go of their life, just to end the pain of suffering.

The short documentary navigates this emotionally exhausting experience through Anggo, who consistently met with hurdles along the way, just to see everything go back to zero, or when Tes occasionally had difficulties from time to time, and would rather end this all. The short documentary reflects on both ends and shows how it is still difficult to give up despite the many sacrifices they have made. But in the end, their relationship with each other is what Martinez’s Si Tes at Si Anggo shows that their perseverance and Anggo’s love for Tes can make all the sacrifices worth it in the end. — Christ Dustly Go Tan

Watch the 37th Gawad Alternatibo Documentary Category at Cinemata now!

Animation Category

Official Publicity Material of the 37th Gawad Alternatibo Animation Category Online Streaming on Cinemata | Courtesy of Cinemata

farther, closer, farther

Directed by Jillian Abby D. Santiago

Sometimes, no matter how far you think you’ve gone, there are people, especially the ones you love, who stay just beyond your reach. Time doesn’t always mend that space in between; it can stretch it wider, turning the ache into something quiet but sharper. farther, closer, farther moves through that ache, tracing the strange pain of loving someone who has drifted so far that even memory becomes distant. This animated film doesn’t just try to close the distance; it sits in it, feeling the pull between what was once near and what now feels impossibly far.

Film still from farther, closer, farther

At its core, the story faces the slow breaking that happens when a parent becomes a presence of absence. Through a young girl’s eyes, we follow a journey through vast skies and endless seas. Her search is both a motion and a feeling, shaped by memories that flicker like light through water. She moves not to find, but to understand, to touch what time has changed.

The film’s use of mixed media animation deepens that sense of loss. Textures overlap: paper, illustration, and pictures, as though the story itself is trying to remember what it once was. You can sense the creator’s hand in every frame. In just five minutes, Jillian Abby D. Santiago’s farther, closer, farther carries the weight of a lifetime: the ache of searching, the quiet endurance of love, and the fragile hope that maybe, somewhere just past the horizon, love still knows the way home. — Jessica Maureen Gaurano

Unravelled

Directed by Sofia Bianca Chua, Maria Isabella Patricia Manaloto, Avryll Nartates

Acceptance. It’s something we all want, especially when we’re trying to make sense of who we are. When it comes to our sexual or gender identity, that hunger for belonging can run deep. But the hard part is, acceptance often comes with strings attached. You feel the push to adjust yourself, to smooth out the edges, to be easier for others to take in. What should’ve been unconditional turns into something you have to earn.

Unravelled follows Rio as he tries to live through that tension. He’s caught between the ghosts of his past and the weight of wanting to be seen. His journey isn’t only about being accepted by others; it’s about finding a way to accept himself.

Film still from Unravelled

When I first sat down to watch the short film, I expected something heavy, maybe even bleak. Instead, I found something gentler. The film doesn’t shy away from pain, but it lingers in the moments of quiet reflection, the kind that feels real. We like to think that coming out is the end of the road, that once you say it out loud, you’re free. But Unravelled shows that it’s where the work begins: learning to live openly in a world that doesn’t always know how to hold you.

By the end, when Rio takes off the mask (literally and figuratively), it becomes packed with emotion. The single act says what words can’t: acceptance isn’t something you get from others first. It’s something you build from within, piece by piece. The story itself feels simple, but that’s what makes it stay with you. It’s not just a film for those still figuring themselves out but for anyone who’s ever felt split between who they are and who they think they should be. — Jessica Maureen Gaurano

Fly, My Dear

Directed by Mary Angel Adelle Dizon

Fly, My Dear is defined by its style rendered in delicate pencil outlines that feel intentionally understated. Told without dialogue, the film relies solely on its score to communicate a child’s grief and longing for a parent. The simplicity of this approach is precisely what makes it effective through small gestures and pauses, which speak louder than words ever could. Short and bittersweet, Fly, My Dear makes the most of its runtime, trusting its audience to sit with the feelings rather than spelling it out and in doing so, leaves a quiet but lingering impression. — Arri Salvador

Film still from Fly, My Dear

Inbituin

Directed by Ronald Recalde Jr. & Jhon Michel Simon

Even from its opening sequence, Inbituin lights up the screen with its innocent charm. Like an ode to childhood memory and childlike wonder, it tells the story of a boy who encounters a fallen star child. It is a visual feast, even within the limitations of a student film, doing its best to portray a friendship bound by a cosmic connection. With no dialogue aside from narration, the short leans heavily on its score, which can feel repetitive at times. Still, Inbituin finds its strength in sincerity, capturing the beauty of a starry night. — Arri Salvador

Film still from Inbituin

Opportunity

Directed by Eunice Sy

Sometimes, the world decides who we are before we even start. It looks, it assumes, and it closes the door. We get pushed aside, not because we failed, but because no one thought we could stand a chance. But once in a while, something cracks open, a small space where the overlooked can finally step in. That’s the heart behind Opportunity.

Film still from Opportunity

Eunice Sy’s short animated film doesn’t need words to make its point. It lets light, color, and rhythm deliver its message. Around the chicken, the world moves without care: the cages clatter, the other fighters boast. The space feels both alive and heavy, as if hope has pushed just to breathe. When the champion falls, the story shifts. The owner looks down at the chicken, not with warmth, but with a tired sort of decision. That single glance becomes the turning point. No speeches, no grand setup. Just a look and a chance handed to someone who was never meant to have one. From there, the animation swells. Colors sharpen, light bends around movement, and the chicken steps forward.

His steps are slow, but each one is earned. You can sense the weight behind every frame, the years of dismissal pressing against his will to rise. Sy draws emotion not through action, but through stillness, through this, the more we see what’s been hidden all along: strength, the kind that doesn’t ask to be seen, only to be given space. By the end, what stays isn’t victory, but recognition. The chicken stands not as a symbol of conquest, but as proof that being given a chance can be enough to change everything. In three minutes, Sy captures the ache of invisibility and the grace of being noticed at last. — Jessica Maureen Gaurano

Paradise

Directed by Rose Dianalou M. Cruzat

Paradise is, on a technical level, one of the most polished and easily enjoyable among the shorts I've watched. Reminiscent of 2000s teen comedies such as Total Drama and 6teen, its animation is clean and crisp, showcasing a strong command of its craft.

The short film follows a young woman navigating university life as she outgrows her fantasy and infatuation with a movie star and is forced to face the realities of adulthood. While the idea is relatable, her transition feels a bit compressed, relying more on realization than on showing the gradual shift that leads to her decisions.

Film still from Paradise

Understandably, the premise is broadly universal, but Paradise does feel culturally distant and more Western, lacking a strong sense of Filipino identity that might have grounded it more firmly in place. Still, its digital flair left a very strong impression, even if its identity feels more global than local, as one would expect from a Gawad Alternatibo film. — Arri Salvador

Pulang Angui

Directed by Mary Jenica L. Robles

Pulang Angui immediately distinguishes itself through its art style, which resembles illustrations from the children's books of Adarna House. This aesthetic choice is definitely well-matched to its material, grounding the film's visual language in folklore roots.

Film still from Pulang Angui

Drawing from Albay's rich mythos and history, the short weaves a tale of bravery in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. And while the narrative remains straightforward, it recalls the childhood TV shows where folklore and moral lessons were subtly woven in, told through a blend of animation and watercolor-like imagery.

More than anything, Pulang Angui succeeds in honoring the spirit of its inspirations. It may not overcomplicate its story, but its cultural references and visual cohesion give it a resonance that extends beyond its runtime. — Arri Salvador

The Naughty and The Hungry

Directed by Mark Ellison Dimzon Mungcal

The Naughty and the Hungry is exactly what its title promises: a naughty dog and a hungry human crossing paths and getting into a series of hijinks. Framed as a screwball comedy, the short relies heavily on physical gags and exaggerated reactions, but places them within a bleak apocalyptic setting. The contrast is occasionally effective, even if it doesn’t fully settle into a consistent tone.

Beneath the comedy is a simple story about empathy and shared survival in a cold, unsympathetic world. The human is driven by hunger and necessity, the dog by instinct and mischief, yet their brief connection gestures toward the possibility of kindness even after society has already collapsed. The short is at its strongest when it resists the urge to keep being funny.

The animation is serviceable for a student film, if not especially expressive. At times, it echoes Free Jimmy, both in its visual approach and its uneasy balance between cartoon humor and grim circumstances. While the short does not push its ideas far enough, its sincerity and modest ambitions give it a quiet charm. — Arri Salvador

Film still from The Naughty and The Hungry

What if There is Nothing in the End

Directed by Jesus Christopher Gallegos

This film was made with the assistance of AI. I won’t dwell too long on that, but it’s hard not to see what that choice says about where art is going. AI taking over creative spaces might look clever, but it strips art of its pulse, that rough, honest sincerity that only comes from being alive. Progress in technology doesn’t always mean progress in meaning. A machine can copy tone, structure, even a kind of emotion, but it can’t live what it’s trying to show. That’s the gap. Art without life inside it feels hollow, and this film makes that clear.

Film still from What if There is Nothing in the End

The story itself had promise. What if There is Nothing in the End wanted to face death, life, and the weight of being, seen through an ambulance driver named Alex. It could’ve shown how a person keeps moving when nothing feels worth it, how meaning shows up in the act of getting through the day. But what we get instead feels thin, like an outline of something once breathed. The dialogue circles ideas but never touches the ground. It misses that grain of truth: the contradictions, the pauses, the pain that slips between words. What’s missing most is the soul of place. There’s no Filipino heartbeat here; no sign of our humor, our struggle, or even small daily tenderness. It’s universal only because it’s vague. In the end, the film plays more like an experiment than an expression. Maybe it is impressive, but it doesn’t move. It reminds us why storytelling matters, because it’s made with people, not programs. Without that human touch, no machine can reach the truth; it’s only pretending to know. — Jessica Maureen Gaurano

Watch the 37th Gawad Alternatibo Animation Category at Cinemata now!

The 37th Gawad Alternatibo was held last October 6 to 10, 2025. Online streaming of featured finalists at Cinemata started last October 23 and will last until January 4, 2026.

Cinemata, a video platform and community for human rights and environmental justice films in the Asia-Pacific, is the official streaming platform of the Gawad Alternatibo.