Is ‘Food Delivery: Fresh from the West Philippine Sea’ Singing the Same Tune as the Government?

Is ‘Food Delivery: Fresh from the West Philippine Sea’ Singing the Same Tune as the Government?

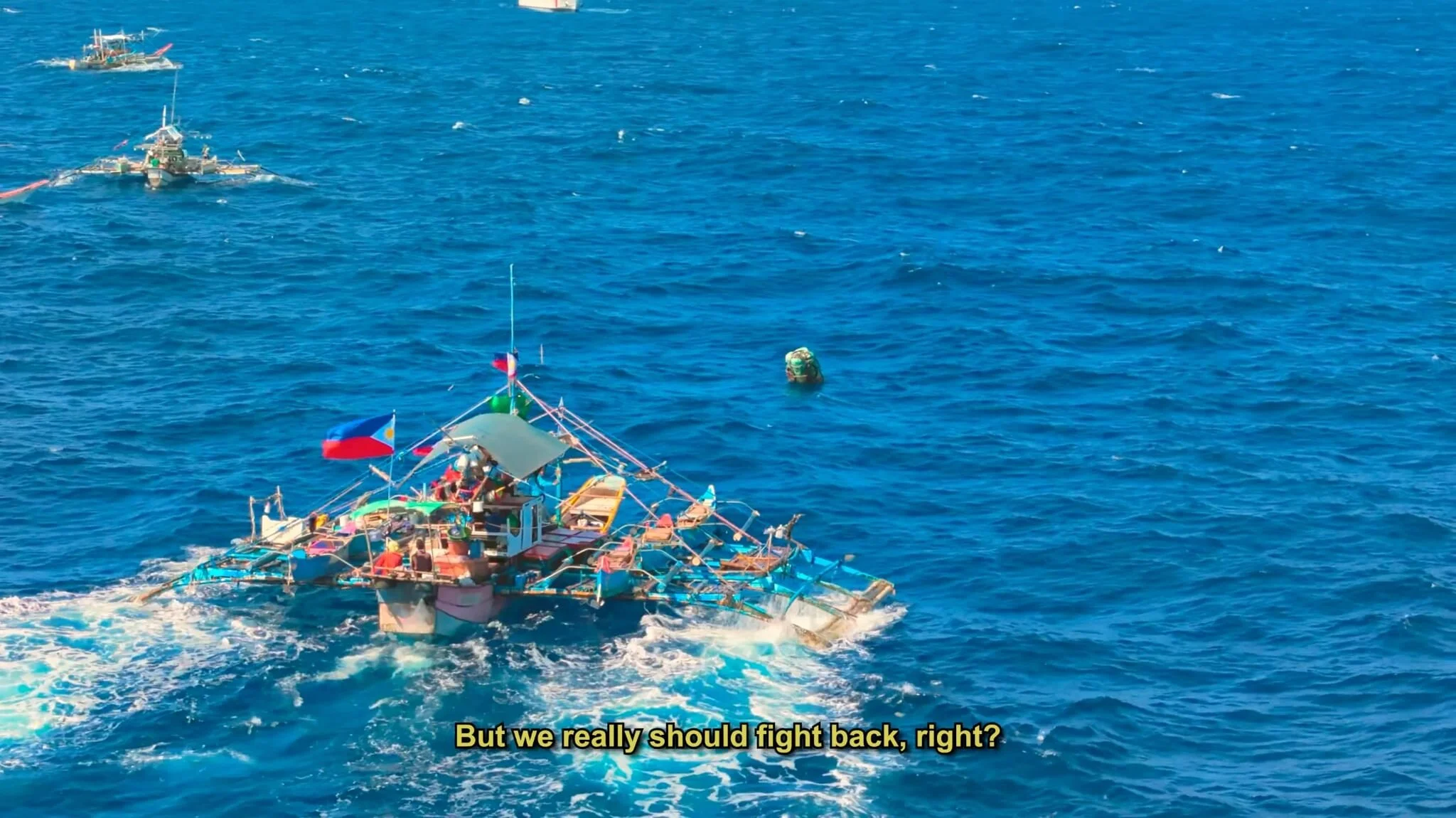

Arnel Satam in ‘Food Delivery: Fresh from the West Philippine Sea’

| Film still from Food Delivery.

On August 23, 2024, the film Alipato at Muog (Flying Embers and a Fortress) was rated X by the MTRCB, as it was found to “undermine confidence in the government.” The award-winning documentary by filmmaker-activist JL Burgos focuses on his family’s search for his brother Jonas Burgos, an activist who was abducted by members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) in broad daylight on April 28, 2007. Among a myriad of spooks in uniform who appeared in this film, a squat little man named Eduardo Año stands out. At the time, he was the head of the intelligence service of the AFP. The infamous intelligence service is often employed in black operations such as enforced disappearances. Instead of being investigated and punished for his involvement in human rights violations such as forced abductions and torture, Año has risen through the ranks of the military and state hierarchy to become National Security Adviser. An attempt to protest his confirmation as Chief of Staff is shown in the film. Jonathan Malaya, Año’s colleague at the NSC, took to the media to defend Año and the military, downplaying the gravity of Jonas’ disappearance and belittling the film. This is the level of persecution and censorship that Alipato at Muog faced. Following a sustained protest campaign, the X rating was overturned. Now, the film has won several awards, most notably the coveted FAMAS and Gawad Urian.

Other Filipino documentaries, such as Asog and Lost Sabungeros, have also faced similar cases of censorship, with theater operators sabotaging screenings and release schedules being pulled. Food Delivery: Fresh From the West Philippine Sea has also faced similar threats. Directed by Baby Ruth Villarama, the documentary follows the stories of Filipinos caught up in the dispute between the Philippines and China over their maritime rights in the South China Sea. The film’s initial release in March 2025 as part of the Puregold Cinepanalo Film Festival was pulled. The eventual premiere of Food Delivery at the Doc Edge festival in New Zealand also faced an attempt to have it pulled. Villarama shared in an interview with the media that it was, in fact, the Chinese Consulate in New Zealand that contacted the festival organizers, who refused their request to pull the film from screening. The Chinese Consulate claims that the film is “rife with disinformation and false propaganda” and that it’s a tool to pursue “illegitimate claims.”

As we see increasing attacks against filmmakers and cultural workers amid this suffocating environment of censorship and distortion, we must ask: Where does this film stand? Who stands to benefit from its release? Who benefits from its censorship?

Villarama and co didn’t seek to create a film about geopolitics. They merely sought to tell personal stories of the people caught up in the brewing conflict in the West Philippine Sea. The film focuses on the Philippine Coast Guard’s mission to resupply the settlers in the Philippine-occupied portions of the disputed islands, as well as a group of fisherfolk whose livelihood is threatened by the constant harassment of the Chinese Coast Guard. Despite the emphasis on the personal, the political shines through in every frame and throughout its release. The choice to focus on the Philippine Coast Guard and AFP for a third of the documentary is, in and of itself, a political choice, whether or not the filmmakers were conscious of this at the time and whether or not it is apparent to the audience.

Speaking of form, the medium of film is rife with various techniques that build up a language of imagery, symbolism, and semiotics, all of which serve the story of the film. When expertly employed, this can subconsciously affect and restructure the audience’s perception of people, things, and events. This is the power of cinema, and this power must be used responsibly by those who have the skill. Film inherently builds a language through sound, picture, and time, and this language varies through different genres and different films. Through careful articulation, you can also shape narratives that build up a distinct viewpoint.

Film still from Food Delivery.

In Food Delivery, we begin with scenes of AFP soldiers and the Philippine Coast Guard engaged in a resupply mission—immersive shots, and epic, heroic music underscore the scene. The gravity of the situation is purely built up through the skillful use of editing and scoring, tension is constructed by portraying the Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) ships as intimidating, and the lay of the land is illustrated by expertly animated map scenes that display the boundaries of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) which the Philippines won through an UNCLOS arbitral tribunal ruling in 2016. All in all, it’s well done in terms of form. But while watching the feeling of being led on to a certain conclusion couldn’t leave me. There are several shots in the film that portray the AFP as heroic. There’s a conscious choice to play up an image of the courageous defenders. This conflicts with what many people know about the bloody record of the AFP. According to KARAPATAN, from 2022 to 2025, the present Marcos administration had been responsible for thousands of cases of human rights violations, including 14 enforced disappearances, 134 counts of extrajudicial killings, and 822 cases of arbitrary and illegal arrests. Despite their new rhetoric claiming “peace and unity” and “respecting international humanitarian law,” their actions now provide us with no reassurance.

The scenes of the Philippine Coast Guard staff show us the human faces behind the guns and ships—they seem to be most worried about their salaries. With the score and editing, the filmmakers want to imply or imbue heroism upon them. This is not what we get.

Film still from Food Delivery.

The heroism appears later in the film when we finally immerse ourselves with the fisherfolk communities who are most affected by the geopolitical tensions building up in our waters. We are introduced to Arnel Satam and several other fisherfolk who venture out to the waters near Bajo de Masinloc where they fish. Satam and his fellow fishermen tell the filmmakers that ever since geopolitical tensions flared up, they could no longer fish in the more prosperous waters near Bajo de Masinloc because of the relentless Chinese Coast Guard patrols. To me, this is where Food Delivery shines. Had they primarily focused on the fisherfolk and their struggle for livelihood amidst the growing inter-imperialist conflict, it would elevate the popular understanding of the problem of national sovereignty. The question of land, water, and livelihood is ultimately tied up with the question of national sovereignty. A memorable scene features a fisherman telling us that if their livelihoods were fully cut off by China or whoever else, the fisherfolk would be willing to fight to the finish.

Film still from Food Delivery.

It’s infuriating to see your people being bullied and our sovereignty disrespected, and this is the point we’re all getting at here: that we should fight for our right to the land and the seas. However, there’s something Food Delivery isn’t showing. Presently, the Philippines is littered with foreign bases and foreign troops. As of writing, there are nine bases of the United States and dozens more undeclared or secret sites found within our territory. The overt and covert American presence tramples over our sovereignty day after day after day. Each moment an American base stays for even a minute on Philippine soil, our sovereignty is being violated. Any story about national sovereignty should begin here because it is precisely this US presence that provokes its imperialist rivals like China.

The US is presently consumed with plans to beef up its military, explicitly stating in its National Security Strategy that it desires to create the “world’s most powerful, lethal and technologically advanced military.” US President Donald Trump continues to spew interventionist and inflammatory comments about their designs for Venezuela, Greenland, Iran, Palestine, and Cuba. Soon after Food Delivery and a slew of documentaries and films about the West Philippine Sea premiered—including Hiyas ng Escoda, a TV documentary, and Alon ng Kabayanihan, a trailer which also features characters from the Coast Guard and defiant fisherfolk—the US and the Philippine governments unveiled the Task Force Philippines last October 2025. Composed of Filipino and American troops, the task force is focused on “cooperation that will deter Chinese coercion.” Why do they need the extra deterrence? They already have thousands of US troops operating on Philippine soil. They already have medium-range missiles and anti-ship systems such as the Typhon and NMESIS set up in strategic points in the Philippines. War games, military exercises, and military agreements between US troops, Japanese troops, Australian troops, and Filipino troops occurred at an unparalleled and unprecedented frequency with constant buildup in the last two years. What more “deterrence” could we need?

It’s at this point that the full picture hidden from the overall story of Food Delivery emerges. It turns out that this is not as simple a tale as David and Goliath. The enemy from within and without is in fact the one posing as a friend. When we talk of empires that violate the national sovereignty of the Philippines due to their hunger for resources and new markets, we have no other culprit as bellicose and arrogant as the United States of America. The “ironclad partnership” they boast about between themselves in the Philippines is one that was forged by a genocidal war against our people and decades upon decades of tyranny and deceit. They are watering at the mouth for the natural resources waiting to be tapped at the bottom of our contested economic zone, such as the mineral and gas deposits. A new gas deposit consisting of 98 billion cubic feet of gas was uncovered near the shores of Palawan earlier this January. There is bound to be even more untapped potential just underneath our feet. These resources should go to the Filipinos, not to China, and certainly not to the United States.

AFP officials at the first screening of Food Delivery on July 27, 2025. | Taken from the Stratbase Institute website.

A bottomless barrel of AFP spokesmen tour campuses and communities to play up “the Chinese menace” to justify their military spending. Early on in its release, Food Delivery was screened for a conga line of VIPs, diplomats, army officers, politicians, and curiously, think tanks focused on the South China Sea and the Indo-Pacific, such as CIRIS and Stratbase. On the film’s social media pages, numerous short video interviews show high-profile viewers, ranging from actors to government officials, singing their praises. They had much to say about the importance of the film’s message, including NSC Director Eduardo Año—the same man implicated in the disappearance of Jonas Burgos.

A group photo of AFP Command and General Staff Course (CGSC) students with the filmmakers at a special screening of Food Delivery. | Taken from @fooddeliveryfresh on Instagram.

The Task Force West-Philippine Sea, also headed by Año, rolled out screenings of Food Delivery for schools in Palawan, a province that directly faces the West Philippine Sea, and which has two EDCA sites: Antonio Bautista Air Base in Puerto Princesa, and Naval Station Narciso del Rosario in Balacbac Island. As of writing, the military exercises and war games between the AFP and US Army at the strategic points in Palawan, facing the West Philippine Sea and South China Sea, and Batanes, which faces Taiwan, continue without letup. What are you going to do about it?

PCG Commodore Jay Tarriela talking to US Embassy official Y. Robert Ewing at a screening of Food Delivery. | Taken from @fooddeliveryfresh on Instagram.

So, what is Food Delivery’s message and who benefits from it? Other than what’s been presented here, I leave it to the reader to decide for themselves. But I do want to pose this question: When you are singing the same tune as Uncle Sam, the neocolonial mercenary army he created here in the Philippines, and their various operatives at all levels of government and civil society, at what point do we begin to consider that one is actually part of the chorus? At the end of the day, filmmakers are challenged to shed their pretenses of neutrality, and audiences are challenged to be more critical. The world that the lens is reflecting is not neutral. If there’s anything to learn from the opening weeks of 2026, narratives serve an important role in how conflicts begin and end.